It is told that there was once a man who through his misdeeds deserved the punishment which the law meted out to him. After he had suffered for his wrong acts he went back into ordinary society, improved. Then he went to a strange land, where he was not known, and where he became known for his worthy conduct. All was forgotten. Then one day there appeared a fugitive that recognized the distinguished person as his equal back in those miserable days. This was a terrifying memory to meet. A deathlike fear shook him each time this man passed. Although silent, this memory shouted in a high voice until through the voice of this vile fugitive it took on words. Then suddenly despair seized this man, who seemed to have been saved. And it seized him just because repentance was forgotten, because the improvement toward society was not the resigning of himself to God, so that in the humility of repentance he might remember what he had been. For in the temporal, and sensual, and social sense, repentance is in fact something that comes and goes during the years. But in the eternal sense, it is a silent daily anxiety. It is eternally false, that guilt is changed by the passage of a century. Soren Kierkegaard, Purity of Heart is to Will One Thing (Chapter 2: Remorse, Repentance, Confession: Eternity’s Emissaries to Man) 1847

If you are a student caught up in your academic pursuits in a senior division religion course, you may find here a way into this globally significant writer’s precise and passionate understanding of Christianity. If you are a graduate student trying to grasp what Niebuhr or Tillich or Barth means by his praise and criticism of Kierkegaard, you may find here, particularly in the notes, a way to fuller discussion of these relationships. If as a pastor or therapist you are involved in trying to heal the human spirit, you may find here an unparalleled diagnosis of the architectonics of human despair along with a prescription that encompasses human psychological wisdom and yet appeals to divine revelation. If you are a member of a community of faith in this time of great religious confusion, you may find here the basis for what became a scathing critique of the cultural accommodations of established Christianity and a pointing toward a recovery of biblical faith. Most importantly, if you are simply a human being trying to find a way to navigate the turbulent currents of life’s becoming, you may find here guidance for your venture, albeit put in the poetry of paradox.

Existing Before God, Søren Kierkegaard and the Human Venture Preface Paul R Sponheim © 2017 Fortress Press

Philosophy and religion were at odds since Descartes wrote his Principles of Philosophy which called for doubting everything. Soren Kierkegaard questioned this axiom in his book Fear and Trembling as did his pseudonymous author Johannes Climacus.

When the question about truth is asked objectively, truth is reflected upon objectively as an object to which the knower relates himself. What is reflected upon is not the relation but that what he relates himself to is the truth, is true. If only that to which he relates himself is the truth, the true, then the subject is in the truth. When the question about truth is asked subjectively, the individual’s relation is reflected upon subjectively. If only the how of this relation is in truth, the individual is in truth, even if he in this way were to relate himself to untruth. Let us take the knowledge of God as an example. Objectively, what is related upon is that this is the true God; subjectively, that the individual relates himself to a something in such a way that his relation is in truth a God-relation. The existing person who chooses the objective way now enters upon all approximating deliberation intended to bring forth God objectively, which is not achieved in all eternity, because God is a subject and hence only for subjectivity in inwardness. The existing person who chooses the subjective way instantly comprehends the dialectical difficulty because he must use some time, perhaps a long time, to find God objectively. He comprehends this dialectical difficulty in all its pain, because every moment in which he does not have God is wasted. Soren Kierkegaard, (Johannes Climacus) Concluding Unscientific Postscript 1846, Hong p. 199-200

Here is a list of books that lead up to Kierkegaard’s time for your examination.

Soren Kierkegaard is known as “The father of existentialism”.

Not merely in the realm of commerce but in the world of ideas as well our age is organizing a regular clearance sale. Everything is to be had at such a bargain that it is questionable whether in the end there is anybody who will want to bid. Every speculative price-fixer who conscientiously directs attention to the significant march of modern philosophy, every Privatdocent, tutor, and student, every crofter and cottar in philosophy, is not content with doubting everything but goes further. Perhaps it would be untimely and ill-timed to ask them where they are going, but surely it is courteous and unobtrusive to regard it as certain that they have doubted everything, since otherwise it would be a queer thing for them to be going further. This preliminary movement they have therefore all of them made, and presumably with such ease that they do not find it necessary to let drop a word about the how; for not even he who anxiously and with deep concern sought a little enlightenment was able to find any such thing, any guiding sign, any little dietetic prescription, as to how one was to comport oneself in supporting this prodigious task. “But Descartes did it.” Descartes, a venerable, humble and honest thinker, whose writings surely no one can read without the deepest emotion, did what he said and said what he did. Alas, alack, that is a great rarity in our times! Descartes, as he repeatedly affirmed, did not doubt in matters of faith. He did not cry, “Fire!” nor did he make it a duty for everyone to doubt; for Descartes was a quiet and solitary thinker, not a bellowing night-watchman; he modestly admitted that his method had importance for him alone and was justified in part by the bungled knowledge of his earlier years. Soren Kierkegaard, (Johannes Silentio) Fear and Trembling 1843 Preface, tr. Walter Lowrie 1941

In 1955 Jean-Paul Sartre presented an address entitled “The Singular Universal” at a UNESCO conference dedicated to the 100th anniversary of Kierkegaard’s death. The conference was billed as “Kierkegaard Living”. Sartre said death turned Kierkegaard into an object of knowledge. He wondered if it is possible to access the subjectivity of someone who has died. Hegel believed we are determined by our historical circumstances. This would make Kierkegaard a mere moment in the Hegelian system. Sartre thought Hegel never discovered the individual’s subjective truth. Every individual is born into a set of socioeconomic, cultural, moral, and religious conditions that are not of his choosing. This is a given. The question becomes one of the difference between historical necessities and historical accidents. Does a person’s given absolutely determine his future? Sartre says in choosing a person surpasses his original contingency. One can become more that what one was when one was in the world. Kierkegaard’s writings seem to fail to convey knowledge of his inwardness; they only help readers acquire knowledge of their own inwardness. Kierkegaard’s struggle to find a place for subjectivity and freedom in the face of the Hegelian system seems to serve as an allegory for Sartre’s own struggle. The universal creates the singular and from another the singular creates the universal.

Sartre’s View of Kierkegaard as Transhistorical Man 2006 by Antony Aumann (Northern Michigan University) Journal of Philosophical Research 31 (2006) 361-372

translated by Barbara Foxley (1860 – 1958) 1895 (the rest is on Archivedotorg

Rousseau becomes tutor to young Emile. His method of teaching was unique in many ways and his questions are still important today.

Witty minds have not failed to remark, on the derision expressed by nature, in that she appoints, on this earth, the cattle in the field to be more learned than we, and the bird in the heavens more wise. But has it not been her intention that man should owe his prerogatives to the social affections; should early accustom himself to reciprocal dependence; seeing betimes the impossibility of dispensing with others? Wherefore has she sought to compensate death, not by a cold mechanism, but by the soft and ardent inclination of love? Wherefore has her Author provided by laws, that marriage should spread, and that families, by ingrafting with families, should form new bonds of friendship? Wherefore are his goods so differently appointed to the earth and its dwellers, but to render them social? The fellowship and inequality of men are also nowise among the projects of our wit. They are no inventions of policy, but designs of Providence, which, like all other laws of nature, man has partly misunderstood, and partly abused.

From The Merchant by Hamann

If I wanted to be Lessing’s follower by hook or by crook, I could not; he has prevented it. Just as he himself is free, so, I think, he wants to make everyone free in relation to him, declining the exhalations and impudence of the apprentice, fearful of being made a laughingstock by the tutors: a parroting echo’s routine reproduction of what has been said.

Soren Kierkegaard Concluding Unscientific Postscript 1846, 1992 P. 72

|Hermann Samuel Reimarus 1694-1768.

Has he accepted Christianity, has he rejected it, has he defended it, has he attacked it? 65 With regard to the religious, he always kept something to himself, something that he certainly did say but in a crafty way, something that could not be reeled of by tutors, something that continually remained the same while it continually changed form, something that was not distributed stereotyped for entry in a systematic formula book, but something that a gymnastic dialectician produces and alters and produces, the same and yet not the same. It was downright odious of Lessing continually to change the lettering in connection with the dialectical, just the way a mathematician does and thereby confuses a learner who does not keep his eye mathematically on the demonstration but is satisfied with a fleeting acquaintance that goes by the letter. It was shameful for Lessing to embarrass those who were so exceedingly willing to swear to the master’s words, so that with him they were never able to enter the only relation natural to them: the oath-taking relation. It was shameful of him not to state directly, “I am attacking Christianity,” so that the swearers could say, “We swear.” It was shameful of him not to state directly, “I will defend Christianity,” so that the swears could say, “We swear.”

Soren Kierkegaard enjoyed the writings of Lessing. Kierkegaard wrote about him in his Concluding Unscientific Postscript (1846) tr Hong p. 68

The same thing has been said about Kierkegaard.

Lessing closed himself off in the isolation of subjectivity, he did now allow himself to be tricked into becoming world-historical or systematic with regard to the religious, but he understood, and knew how to maintain, that the religious pertained to Lessing and Lessing alone, just as it pertains to every human being in the same way, understood that he had infinitely to do with God, but nothing, nothing to do directly with any human being. p. 65 Lessing has said that contingent historical truths can never become a demonstrations of eternal truths of reason, also that the transition whereby one will build an eternal truth on historical reports is a leap. I shall now scrutinize these two assertions in some detail and correlate them with the issue of Fragments: Can an eternal happiness be build on historical knowledge?

Soren Kierkegaard enjoyed the writings of Lessing. Kierkegaard wrote about him in his Concluding Unscientific Postscript (1846) tr Hong p. 93

Lessing opposes what I would call quantifying oneself into a qualitative decision; he contests the direct transition from historical reliability to a decision on an eternal happiness. He does not deny that what is said in the Scriptures about miracles and prophecies is just as reliable as other historical reports, in fact, is as reliable as historical reports in general can be. Concluding Unscientific Postscript Hong p.96

The question of the means by which Freedom develops itself to a World, conducts us to the phenomenon of History itself. … Even regarding History as the slaughter-bench at which the happiness of peoples, the wisdom of States, and the virtue of individuals have been victimised — the question involuntarily arises — to what principle, to what final aim these enormous sacrifices have been offered. Hegel’s Philosophy of History III. Philosophic History Sec. 24

In the course of this experience it becomes evident to self-consciousness that life is as essential to it as is sheer self-consciousness. In immediate self-consciousness the simple I is an object that is absolute, albeit one that in itself, as is evident to us, is absolutely mediative, and has the sustainment of its independence as an essential moment. Self-consciousness’s initial experience results in the dissolution of this simple unity; this sets the stage for the emergence of a pure self-consciousness and also a consciousness that doesn’t exist purely for itself but rather for one other than it, the latter being matter-of-factly existent in the manner of a thing. Both moments are essential, although, starting out as unequal and antagonistic, their reflection into unity having not yet taken place, they embody conscious existence in contrary ways: the one is independent, existence-for-self being to it essential; the other is dependent, existing in relation to an other that’s essential to it. The former is master, the latter slave. Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit 1807 IV.A. Self-Consciousness Dependent and Independent: Mastery and Servitude Sec. 36

If a German philosopher follows his inclination to put on an act and first transforms himself into a superrational something, just as alchemists and sorcerers bedizen themselves fantastically, in order to answer the question about truth in an extremely satisfying way, this is of no more concern to me than his satisfying answer, which no doubt is extremely satisfying-if one is fantastically dressed up. But whether a German philosopher is or is not doing this can easily be ascertained by anyone who with enthusiasm concentrates his soul on willing to allow himself to be guided by a sage of that kind, and uncritically just uses his guidance compliantly by willing to form his existence according to it. Concluding Unscientific Postscript to Philosophical Fragments by Soren Kierkegaard, 1846, Hong 1992 p. 191

Another trick is to take a proposition which is laid down relatively, and in reference to some particular matter, as though it were uttered with a general or absolute application; or, at least, to take it in some quite different sense, and then refute it. Aristotle’s example is as follows: A Moor is black; but in regard to his teeth he is white; therefore, he is black and not black at the same moment. This is an obvious sophism, which will deceive no one.

This trick consists in stating a false syllogism. Your opponent makes a proposition, and by false inference and distortion of his ideas you force from it other propositions which it does not contain and he does not in the least mean; nay, which are absurd or dangerous. It then looks as if his proposition gave rise to others which are inconsistent either with themselves or with some acknowledged truth, and so it appears to be indirectly refuted. This is the diversion, and it is another application of the fallacy non causae ut causae.

The Art of Controversy by Arthur Schopenhauer

“For all his philosophical and literary interests, Kierkegaard was at heart a preacher, or better still, in the true sense of the word an evangelist, although he always insisted that he wrote as one ‘without authority’.” Key thinkers in Christianity, Edited by Adrian Hastings Alister Mason & Hugh Pyper, 2003.

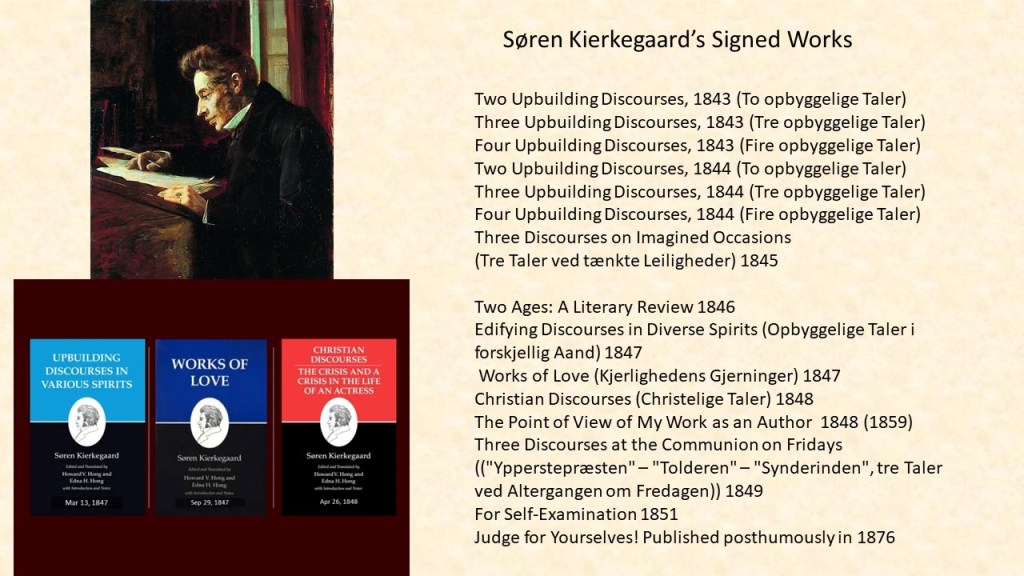

Two Upbuilding Discourses 1843 by Soren Kierkegaard (text)

Listen to Genius recording from Two Upbuilding Discourses 1843

Many good things are talked about in these sacred places. There is talk of the good things of the world, of health, happy times, prosperity, power, good fortune, a glorious fame. And we are warned against them; the person who has them is warned not to rely on them, and the person who does not have them is warned not to set his heart on them. About faith there is a different kind of talk. It is said to be the highest good, the most beautiful;, the most precious, the most blessed riches of all, not to be compared with anything else, incapable of being replaced. If one person went to another and said to him, “I have often heard faith extolled as the most glorious good: I feel though that I do not have it; the confusion of my life, the distractions of my mind, my many cares, and so much else disturbs me, but this I know, that I have but one wish, one single wish, that I might share in this faith” (10-11)

Fear and Trembling 1843 by Soren Kierkegaard (full text)

Let us consider a little more closely the distress and dread in the paradox of faith. The tragic hero renounces himself in order to express the universal, the knight of faith renounces the universal in order to become the universal. As had been said, everything depends upon how one is placed. He who believes that it is easy enough to be the individual can always be sure that he is not a knight of faith, for vagabonds and roving geniuses are not men of faith. The knight of faith knows, on the other hand, that it is glorious to belong to the universal. He knows that it is beautiful and salutary to be the individual who translates himself into the universal, who edits as it were a pure and elegant edition of himself, as free from errors as possible and which everyone can read. He knows that it is refreshing to become intelligible to oneself in the universal so that he understands it and so that every individual who understands him understands through him in turn the universal, and both rejoice in the security of the universal. He knows that it is beautiful to be born as the individual who has the universal as his home, his friendly abiding-place, which at once welcomes him with open arms when he would tarry in it. But he knows also that higher than this there winds a solitary path, narrow and steep; he knows that it is terrible to be born outside the universal, to walk without meeting a single traveler. Fear and Trembling – Chapter 4: Problem Two: Is There Such a Thing as an Absolute Duty Toward God?

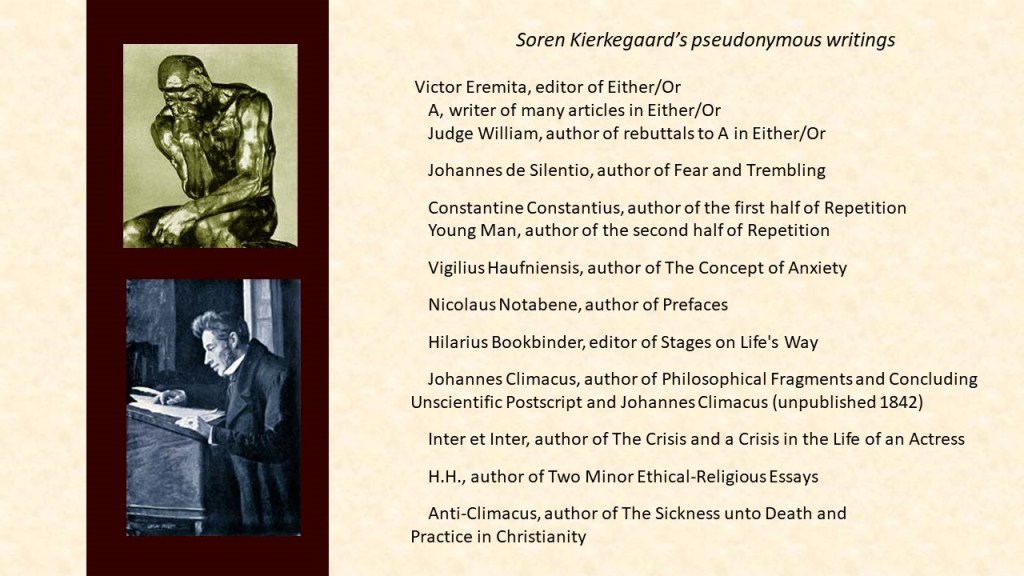

The Stages: The esthetic-sensuous is thrust into the background as something past, a recollection, for it cannot become utterly nothing. The Young Man (thought-depression); Constantin Constantius (hardening through the understanding), Victor Eremita, who can no longer be the editor (sympathetic irony); the Fashion Designer (demonic despair); Johannes the Seducer (damnation, a “marked’ individual). He concludes by saying that woman is merely a moment. At that very point the Judge begins: Woman’s beauty increases with the years; her reality is precisely in time.

The ethical component is polemical: the Judge is not giving a friendly lecture but is grappling with existence, because he cannot end here, even though he can with pathos triumph again over every esthetic stage but not measure up to the esthetes in wittiness.

The religious comes into existence in a demonic approximation (Quidam of the imaginary construction) with humor as its presupposition and its incognito (Frater Taciturnus). Journals and Papers V 5804 (Pap. VI A 41) n.d. 1845 (Eighteen Upbuilding Discourses p. 469)