He asked himself in his melancholic disposition if he can really get married and pursue his writing career at the same time. Grok helped me present Kierkegaard in these three pictures where he eventually decided against marriage in favor of becoming an author.

YouTube user finitude has put Soren Kierkegaard’s book Works of Love to music. It’s well worth the listen.

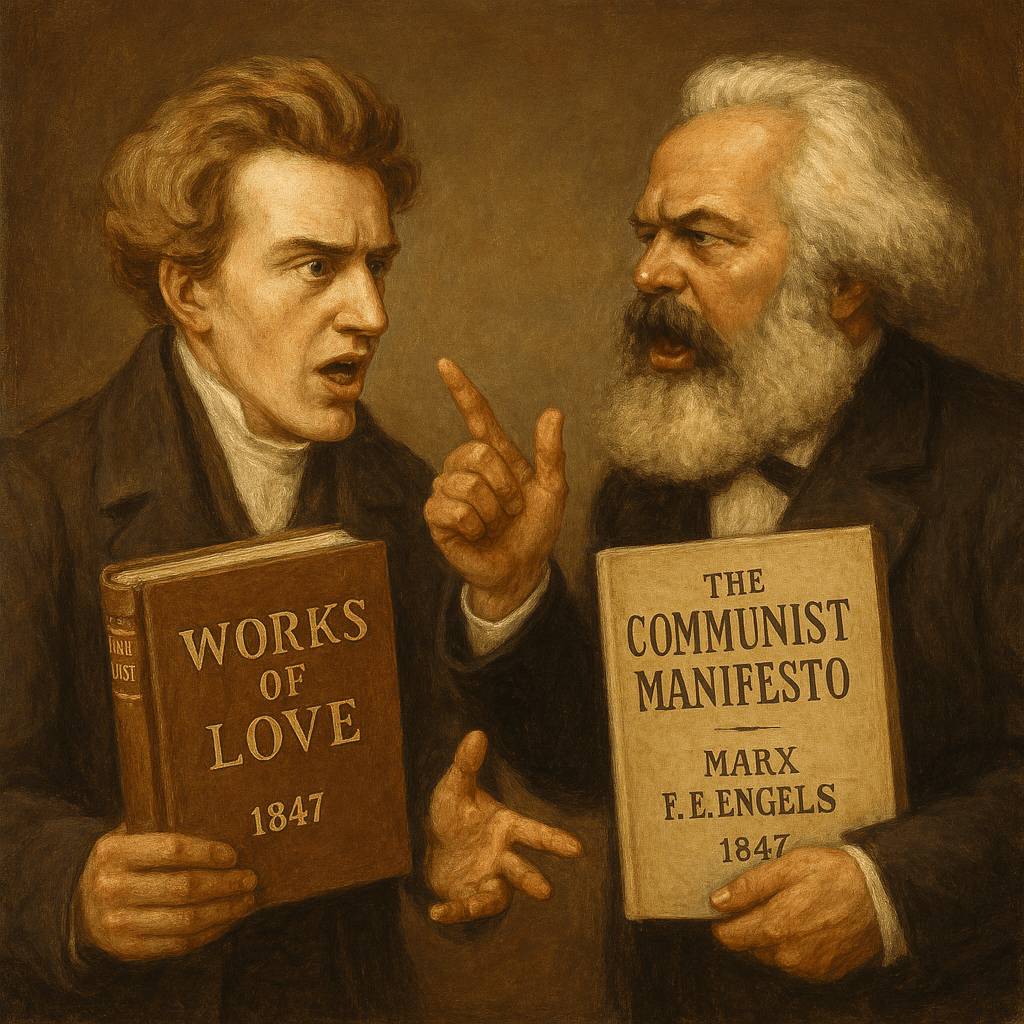

Herbert Read 1893-1968 was an anarchist who was also an art historian and literary critic. He discussed artistic movements throughout the ages in A Coat of Many Colors in 1945. One section was devoted to Soren Kierkegaard where he began: “Kierkegaard, like Marx, is a product by reaction of Hegel. Hegel had at least this virtue : he left behind him a progeny, not of slavish disciples, but of active intelligences, and among these Kierkegaard and Marx represent the widest possible extremes of thought.”

Lotan Harold DeWolf (1905-1986) was professor of systematic theology at Boston University and became Martin Luther King Jr.’s dissertation adviser at Boston University’s School of Theology in 1955. DeWolf published The Revolt Against Religious Reason in 1949 and A Theology of the Living Church in 1953.

He wrote the following in The Revolt Against Religious Reason: “When Barth is charged with “imposing a meaning on the text [of the Epistle to the Romans] rather than extracting its meaning from it,” he declares significantly, “My reply is that, if I have system, it is limited to a recognition of what Kierkegaard called the infinite qualitative distinction between time and eternity, and to my regarding this as possessing negative as well as positive significance .” DeWolf mentioned Kierkegaard very often in his Revolt.

“Because Kierkegaard does not think it possible for living men to attain to the wisdom of eternal truth, so he teaches that it is needful for each of us to live by the authority of a faith not objectively certified but trusted ‘in subjectivity’ i.e. in the individual’s response. Therefore he looks for no higher justification for his faith in the Christian message than that of ‘infinite passion’.” Kenneth Hamilton, The System And The Gospel A Critique Of Paul Tillich New York, Macmillan 1963 p. 51

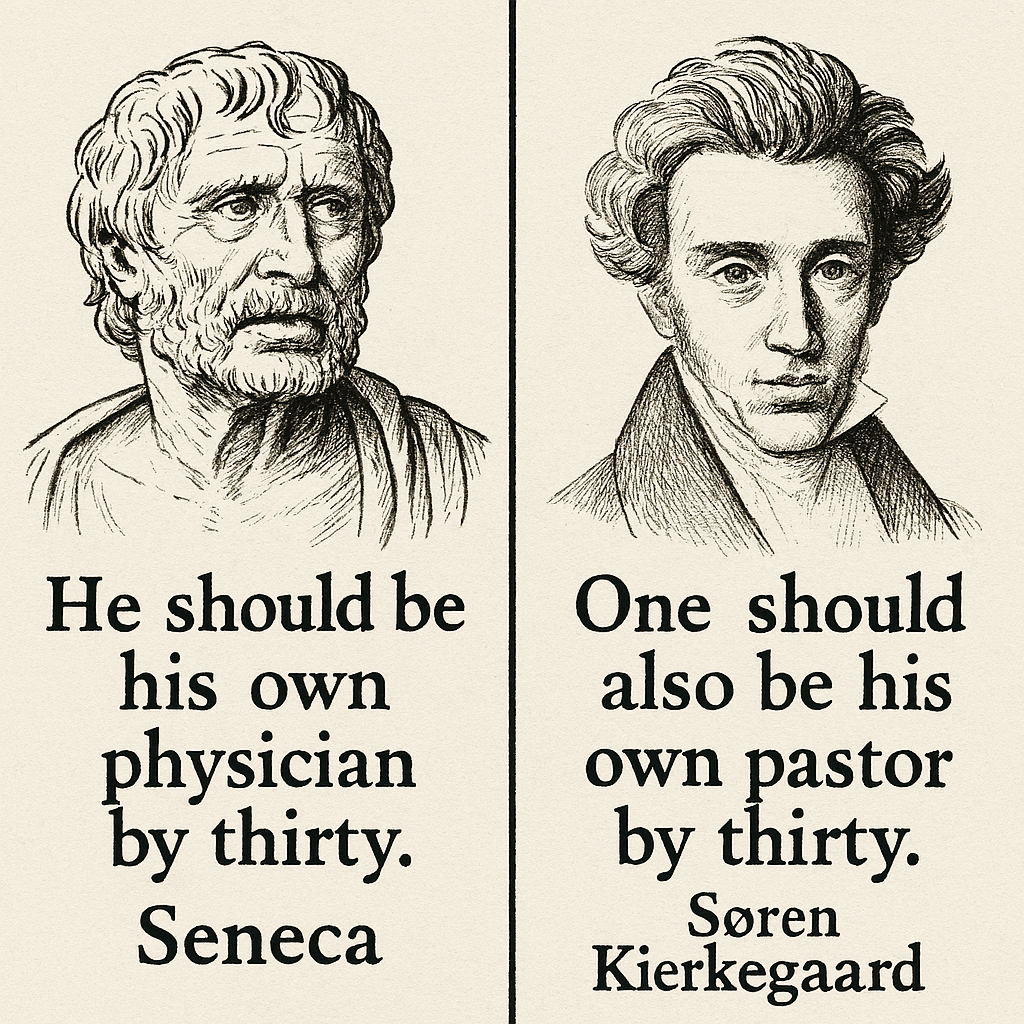

Søren Aabye Kierkegaard lived in Copenhagen, Denmark and studied at the University there from 1830-1840 with the intention of becoming a Christian Lutheran preacher and teacher as his father requested. Sometime during his studies he made the decision that he really didn’t want to preach or teach because he felt he was called to write.

There are some questions for which the appropriate response is not information, a verbal formulation, but an altered way of life. Kierkegaard wrote for readers who could answer the question, “What does it mean to be a Christian.” Jacques Colette said Kierkegaard wrote about the discrepancy between thought and action, knowing and doing, between understanding and existence.

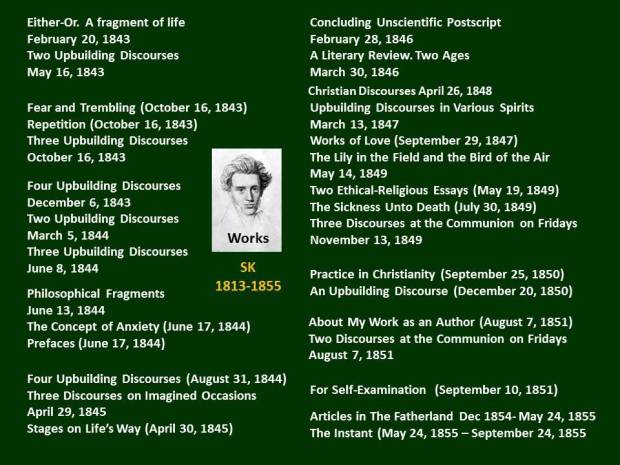

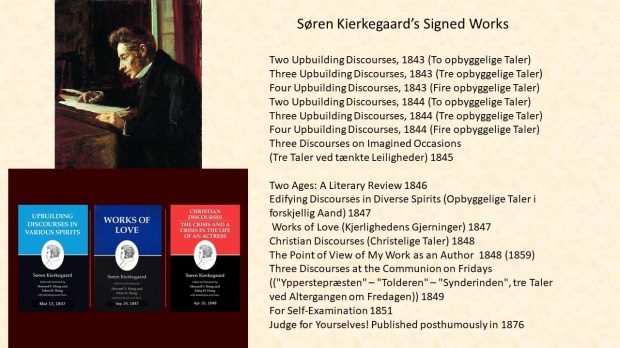

Kierkegaard knows that the art is not to wish but to will. Either/or Vol 2

The story of Kierkegaard’s life is essentially the story of his authorship. His early years seem like the seed-time for a writing career; his last years, when his pen was relatively quiet, are like a benediction upon a work already done. The period between, about nine or ten years, is strenuous but resolute. From 1842 to 1851, Kierkegaard wrote about thirty-five books and the bulk of his twenty-volume journal. When giving an account of his literature, he said it was like a single movement, accomplished in one breath.

Each discourse is calculated to bring the reader, whatever his aesthetic and intellectual capacity, into conversation about religious and Christian concerns. For this reason, among others, Kierkegaard suggests that they should be read in privacy and preferably aloud. Their simplicity and repetitive style make them extremely effective devotional essays. (Paul Holmer – Edifying Discourses a Selection)

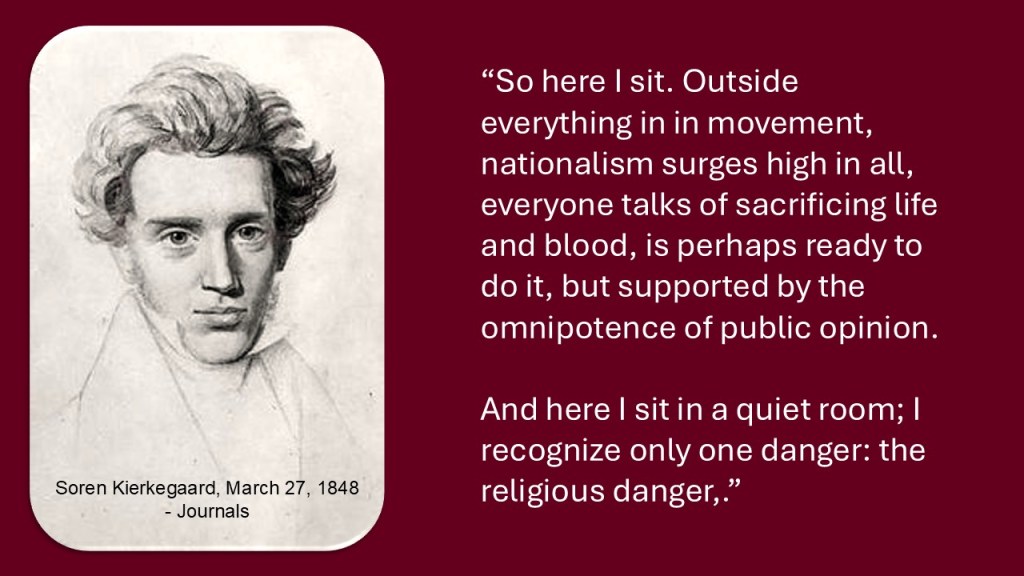

Søren’s father, Michael, wanted him to join the Lutheran priesthood, but Søren had misgivings about preaching and teaching in a Lutheran Church that was supported by the State. The Danish Church was the religion of Denmark and the pastors were paid by the State and cared for by the State. A good Dane would see to it that his children were baptized into the State Church. He was against Christian Nationalism and Enlightenment ideas being used in the religious sphere.

Kierkegaard’s category as a writer was “without authority”, he was neither parson nor professor so he wanted to persuade with the truth alone. He says to the reader, “Judge for Yourself”.

Kierkegaard is regarded as a saint in some churches. Ludwig Wittgenstein and Herbert Read both said he was a saint. Others believe he was a pagan.

Kierkegaard was a deeply Christian thinker, but one who relentlessly challenged the complacency and formalism of the religious establishment. His writings aim to awaken people to the personal, existential demands of real Christian faith. (Chat GPT)

Was Soren Kierkegaard a Christian. AI:Grok answered.

Was Søren Kierkegaard a Christian? Well, buckle up, because the answer’s a wild ride through faith, despair, and a hefty dose of existential flair.

Kierkegaard, a 19th-century Danish philosopher and theologian, is often hailed as the father of existentialism—a movement obsessed with individual existence, freedom, and choice. His life and works were drenched in Christian themes, so if we’re asking whether he believed in Jesus Christ and the Bible, the answer is a resounding yes. He saw Christianity as more than a checklist of beliefs or a ticket to Sunday brunch; for him, it was a radical, soul-shaking way of life centered on faith, love, and a personal showdown with God.

But here’s where it gets juicy: Kierkegaard wasn’t exactly the poster boy for your average churchgoer. He had a bone to pick with the institutional church of his time, slamming it for being a cozy club of dogma and rituals rather than a crucible for authentic faith. To him, true Christianity wasn’t about nodding along to sermons or inheriting your grandma’s religion—it demanded a gutsy, all-in commitment to following Christ, even if it meant flipping the table on societal norms.

His faith was personal, paradoxical, and downright intense. Kierkegaard believed that being a Christian meant staring into the abyss of your own existence, wrestling with freedom and responsibility, and choosing to leap into faith despite the absurdity of it all. He even played literary hide-and-seek, using pseudonyms in his writings to poke at Christianity from every angle, challenging readers to ditch the autopilot and rethink their own beliefs.

So, was Kierkegaard a Christian? Yes—but not the kind who’d fit neatly into a pew. His Christianity was less “hymns and handshakes” and more “screaming into the void about sin, grace, and why God’s probably side-eyeing your half-baked devotion.” If faith had a punk phase, Kierkegaard was its leather-clad, chain-smoking frontman.

Science was to start with no presuppositions, with Socratic ignorance. But Kierkegaard didn’t want to begin in the religious sphere with doubt and with no presuppositions. He wrote the following in Works of Love, “When it is said, “You shall love your neighbor as yourself,” this contains what is presupposed, that every person loves himself. Thus, Christianity which by no means begins, as do those high flying thinkers, without presuppositions, nor with a flattering presupposition, presupposes this. Dare we then deny that it is as Christianity presupposes?” (1847 Hong 1995 p 17) He went on to write about love “presupposing that love is in the other person” and that love builds up because of this presupposition. It’s difficult to begin without presuppositions but it’s more difficult to begin to build up with the presupposition that love is present and to end with the same presupposition. But where was that love present? It is present in the ground of the human being because God has placed it there. Love has to be built up by not doing something to the other person. Love is not built up by tearing down because “no human being is capable of laying the ground of love in the other person. (Works of Love, Hong, p. 219) Spiritually, love is the ground of everything. (224)

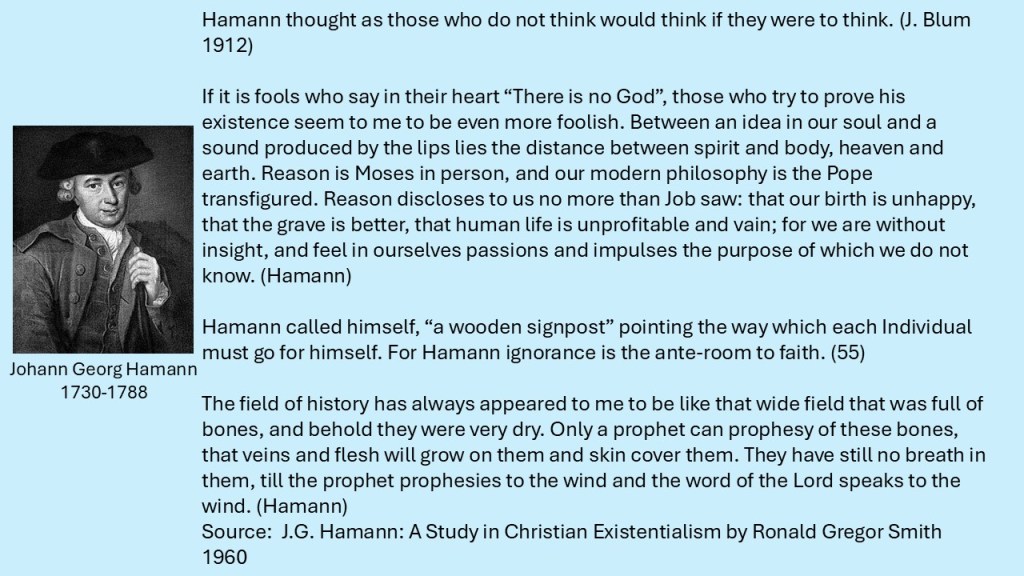

Soren Kierkegaard was inspired by the writings of Johann George Hamann, who wrote against some of the ideas behind the Enlightenment or Aufklärung as the Germans called it.

In 1605 Francis Bacon said, “if a man will begin with certainties, he shall end in doubts; but if he will be content to begin with doubts, he shall end in certainties (Advancement of Learning). Later, in 1620, he said that there are two divisions of philosophy; the investigation of forms (metaphysics) and the investigation of the efficient cause of matter (physics). Parallel to these, let there be two practical divisions; to physics that of mechanics, and to metaphysics that of magic, in the purest sense of the term, as applied to its ample means, and its command over nature. (The New Organon).

- Aristotle’s view that philosophy begins with wonder, not as in our day with doubt, is a positive point of departure for philosophy. Indeed, the world will no doubt learn that it does not do to begin with the negative, and the reason for success up to the present is that philosophers have never quite surrendered to the negative and thus have never earnestly done what they have said. They merely flirt with doubt.

- Soren Kierkegaard, Journals and Papers III 3284 (1841)

Soren Kierkegaard’s search for Truth.

He not only wrote about love, but he wrote about fear and despair as well. Philosophy is proficient in doubting for a few days or weeks and then moving on. But Kierkegaard knew that coming to religious faith was a “task for a whole lifetime” He wondered if we are able to “comprehend how faith entered in us” and how it entered into Abraham as the “Father of faith”. (Fear and Trembling 1843, Hong 1983) p. 7 and 9ff

“By faith Abraham received the promise that in his seed all the generations of the earth would be blessed. Time passed, the possibility was there, Abraham had faith; time passed, it became unreasonable, Abraham had faith. There was one in the world who was given an expectancy. Time passed, evening drew near; he was not contemptible as to forget his expectancy, and therefore he will not be forgotten, either.” Fear and Trembling p. 17 He wrote about expectancy in Fear and Trembling as well as his Upbuilding Discourses in Various Spirits 1847.

Every time I catch my soul not expecting victory, I know I do not have faith. When I know that, I also know what I must do, because although it is no easy matter to have faith, the first condition for my arriving at faith is that I become aware of whether I have it or not. Søren Kierkegaard, Two Upbuilding Discourses 1843, Hong 1990 p 27 (Eighteen Upbuilding Discourses) Edifying Discourses a Selection

The objective faith, what does that mean? It means a sum of doctrinal propositions. . . . The objective faith— it is as if Christianity also had been promulgated as a little system, if not quite so good as the Hegelian; it is as if Christ — aye, I speak without offense— it is as if Christ were a professor, and as if the Apostles had formed a little scientific society. (Postscript 193) “Truth is subjectivity,” he mused, flipping Hegel’s objective systems on their head.

The thing about the spiritual gifts is that they are freely given, there is no human mediator. If there were a human who could give faith to another that same person could take it back again.

That God in incomprehensible reconciling grace lowers himself (has entered into human life, Dasein, as Kierkegaard says) is central alike for Kierkegaard and for Hamann. For Hamann it is also, and precisely, the world which God enters, but for Kierkegaard the place of this event is solely the individual. J G Hamann 1730 1788 A Study In Christian Existence by Ronald Gregor Smith 1960

“Dear Reader: I wonder if you may not sometimes have felt inclined to doubt a little the correctness of the familiar philosophic maxim that the external is the internal and the internal the external. … For my part I have always been heretically-minded on this point in philosophy, and have therefore early accustomed myself, as far as possible, to institute observations and inquiries concerning it. I have sought guidance from those authors whose views I shared on this matter; in short, I have done everything in my power to remedy the deficiency in the philosophical works. Gradually the sense of hearing came to be my favorite sense; for just as the voice is the revelation of the inwardness incommensurable with the outer, so the ear is the instrument by which this inwardness is apprehended, hearing found a contradiction between what I saw and what I heard, then I found my doubt confirmed, and my enthusiasm for the investigation stimulated.” Soren Kierkegaard Either/Or Part 1 Preface

While the understanding despairs, faith presses forward victoriously in the passion of inwardness. Soren Kierkegaard, Concluding Unscientific Postscript to Philosophical Fragments, 1846, Note p. 225 Hong 1992

Philosophical Fragments describes the Christian journey obscurely, without the name of Jesus or the Apostles. Socrates is Kierkegaard’s teacher but Christ is the Teacher who brings the condition for learning along with himself.

When Philip threatened to lay siege to the city of Corinth and all its inhabitants hastily bestirred themselves in defense, some polishing weapons, some gathering stones, some repairing the walls, Diogenes seeing all this hurriedly folded his mantle about him and began to roll his tub zealously back and forth through the streets. When he was asked why he did this he replied that he wished to be busy like all the rest, and rolled his tub lest he should be the only idler among so many industrious citizens. Philosophical Fragments 1844 by Søren Kierkegaard (Preface) Swenson tr

Philosophical Fragments is an interesting book. “Now if the learner is to acquire the Truth, the Teacher must bring it to him; and not only so, but he must also give him the condition necessary for understanding it. One who gives the learner not only the Truth, but also the condition for understanding it, is more than teacher.” Truth is not introduced into the individual from without, but was within him. Philosophical Fragments A Project of Thought

Gregor Malantschuk delivered four lectures to the Soren Kierkegaard Society in Copenhagen in 1951 and published Kierkegaard’s Way to the Truth in 1963 where he said, “It is certainly noteworthy that Kierkegaard’s challenge in Works of Love (September 29, 1847) to solve all problems by self-renunciation appeared only a few months before another challenge to solve all social problems by force – the Communist Manifesto of Karl Marx, which was published in February, 1848.

Kierkegaard and Marx toss out to the world their totally opposite views on the solution of life’s problems. Kierkegaard’s Way to Truth by Gregor Malantschuk 1963 Augsburg Publishing House

Kierkegaard is known for his ideas about despair (mainly through his 1849 book The Sickness Unto Death, but he wrote about despair elsewhere as shown above. Most philosophers who study Kierkegaard point to The Sickness Unto Death when discussing despair. This sickness is not unto death. That’s what Jesus said in John chapter 11 when speaking to Mary about Lazarus. Kierkegaard makes the same point about modern despair. The person who has no eternal consciousness would think of death as the end but for the Christian death is not the end. “One speaks of a mortal sickness as synonymous with a sickness unto death. In this sense despair cannot be called the sickness unto death. But in the Christian understanding of it death itself is a transition unto life. In view of this, there is from the Christian standpoint no earthly, bodily sickness unto death. For death is doubtless the last phase of the sickness, but death is not the last thing. If in the strictest sense we are to speak of a sickness unto death, it must be one in which the last thing is death, and death the last thing. And this precisely is despair.” “The despairing man cannot die; no more than “the dagger can slay thoughts” can despair consume the eternal thing, the self, which is the ground of despair, whose worm dieth not, and whose fire is not quenched.” (The Sickness unto Death, Lowrie)

Just as the physician might say that there lives perhaps not one single man who is in perfect health, so one might say perhaps that there lives not one single man who after all is not to some extent in despair. The Sickness Unto Death

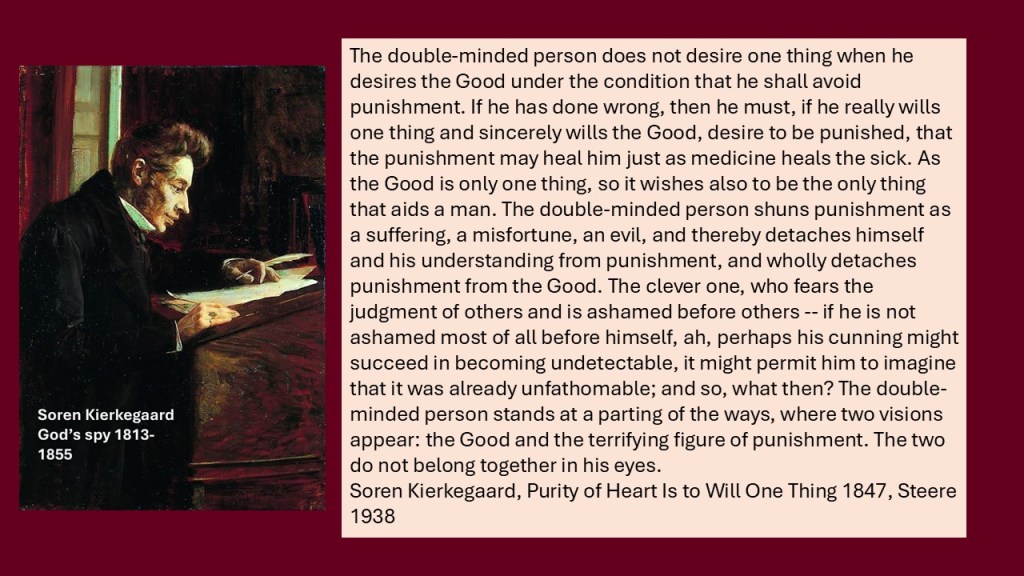

Douglas V. Steere translated part of Kierkegaard’s 1847 book Upbuilding Discourses in Various Spirits in 1938. He called the selection Purity of Heart Is to Will One Thing. Steere called Kierkegaard the Danish Pascal.

Kierkegaard’s first chapter deals once again with the eternal in man. He was concerned with the possibility of the loss of the eternal in the single individual. “Only the Eternal is always appropriate and always present, is always true. Only the Eternal applies to each human being, whatever his age may be. … If there is, then, something eternal in a man, it must be able to exist and to be grasped within every change. … There is a battle of despair that struggles — with the consequences. The enemy attacks constantly from behind, and yet the fighter shall continue to advance.”

“The Good without condition and without qualification, without preface and without compromise is, absolutely the only thing that a man may and should will, and is only one thing.” But the man who wills the Good for the sake of reward does not will one thing, but is double-minded. “The double-minded man stands at a parting of the ways, and sees there two apparitions: the Good, and the Good in its victory, or even in its victory through him.” … “the double-minded person, then, may have a feeling — a living feeling for the Good. If someone should speak of the Good, especially if it were done in a poetical fashion, then he is quickly moved, easily stimulated to melt away in emotion.“

Kierkegaard used this section to write about willing the Good that never changes and is not associated with any other good. Read Purity of Heart here. He emphasized the individual over the crowd because he saw the masses as a diluting force—leveling spirits into conformity, where true passion and faith get lost in the herd. He urges each soul to stand alone before God, leaping into authentic existence amid anxiety and despair. It’s like choosing to dance solo in a ballroom full of synchronized swimmers!

Many say he wasn’t a Christian but he disagreed in his own writings. He was always interested in the religious sphere of existence.

“The situation that now confronts us is one which Kierkegaard has described, and he has prophesied that the time would come when men would be forced to understand that without religion society cannot endure. Are there not signs in the offing that his forecast is being verified?” You can read the book here.

“I am well aware of the fact that a great many parsons, especially in America, if they were to become acquainted with S.K., would indignantly reject him. He is a “corrective,” and they want no correction. Today as in his own age he presents an either/or – either New Testament Christianity/or none at all – and perhaps there are not many willing to face that dilemma.” Walter Lowrie on how Kierkegaard got into English (Repetition, 1941)

We live aesthetically without commitment, but ethical situations demand decisions from us that are decisive.

You can read Soren Kierkegaard at librivox